Another Mysterious Illness Known As MERS Threatens The Globe.

While Ebola is killing Africans ,another mysterious illness known as MERS might turn into the next global pandemic. Or it may fizzle out. For now, public health experts are keeping a close eye on the situation but they haven't declared an emergency yet. Yesterday on BBC news,there were indications that the virus might be worse than Ebola as it leads to Kidney Failure or pneumonia

MERS has already killed 173 people across nineteen countries

Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, was first discovered in 2012 and has a surprisingly high death rate. There have already been 572 confirmed cases and 173 deaths across 19 countries. The majority of the illness has been concentrated in Saudi Arabia.

This week, a second case of the viral disease was identified in the United States, shortly after the first was found earlier this month. (Both were health-care workers who had recently been in Saudi Arabia.) The discovery came after a sudden jump in cases in Saudi Arabia this spring.

The origins and characteristics of MERS are still quite enigmatic. The virus might fade away into oblivion or mutate into a monster. Here's a rundown of what we know so far:

What is MERS?

First off, MERS is not MRSA — the antibiotic-resistant bacteria that's somewhat common in US hospitals.

MERS — or Middle East respiratory syndrome — was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It's caused by a virus called MERS-CoV. Patients with MERS end up with symptoms like coughing, fever, and shortness of breath.

Although MERS doesn't appear to be exceptionally contagious, public-health experts have been tracking it closely because the disease has such a high death rate. So far, about one-third of the people with confirmed cases have died. The majority of MERS has been in Saudi Arabia, although it's spread to 18 other countries, including two recent cases in the US.

There was a sudden spike in MERS cases this spring. WHO

How bad is the situation?

The World Health Organization (WHO) is watching the disease closely and has convened an emergency committee on the threat, which has met five times since July, 2013.

But, so far, the WHO has yet to declare a global health emergency (Public Health Emergency of International Concern) — the way it did for swine flu and polio in recent years. (Declaring such an emergency would allow the organization to make recommendations such as travel or trade restrictions or that people feeling ill delay any international trips.)

So what does it mean? It means that MERS could conceivably get really, really bad. But it's not really, really bad yet.

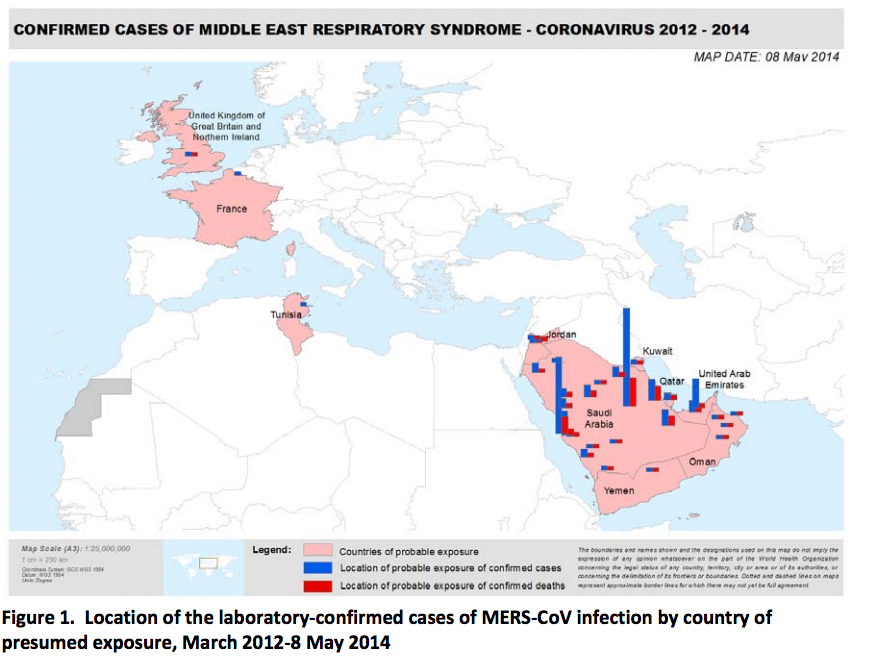

Where is MERS?

More than a dozen countries have confirmed cases so far, including the US. However, most of those people originally caught the virus in Saudi Arabia. (Also, many of those countries don't have anyone who's sick anymore. Oftentimes it's an isolated event. That person then gets better and never infected anyone else.) This map shows where people have been picking up the illness:

The majority of people with MERS caught it in Saudi Arabia. WHO

Where did MERS come from?

Dromedary camel. UIG via Getty Images.

No one is quite sure. So far, evidence of the MERS-CoV virus has been found in bats and dromedary camels (the one-hump kind). It's unclear if the virus actually makes these animals sick, although they could still transmit it either way.

There are millions of camels in the Middle East, where they're used for meat, milk, and racing. It's possible that MERS has been jumping from camels to livestock workers or to people who have eaten raw camel milk or meat. But even that's unclear. Although some MERS cases have appeared in people who work with camels, many others haven't.

Am I going to get MERS?

Right now, the risk is pretty low. But that could conceivably change if the virus mutates.

MERS currently seems to have a pretty low transmission rate — lower than both the flu and SARS. Casual contact — like being on the same plane flight — doesn't seem to be enough to spread the disease. Most documented cases are of people who have been living with or caring for someone with MERS — and those are the only people that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says are at risk. (Many cases in Saudi Arabia are spreading within hospitals.)

MERS currently has a fairly low transmission rate

Here's a picture of how hard it is to spread: after the first confirmed case of MERS in the United States, public-health officials tracked down and tested more than 500 people whom that patient had come in contact with. None of them have turned up positive.

That's why the CDC says that the two cases of MERS in the United States currently "represent a very low risk to the general public in this country." The agency doesn't even recommend that anyone change their travel plans — even if they're going to Saudi Arabia. However, it does recommend that travelers to the Arabian Peninsula take general precautions like washing your hands and avoiding people who are sick.

There is one catch, however: viruses can — and do — mutate. The MERS virus is mutating much more slowly than, say, the seasonal flu virus, but you never know what a random mutation might bring.

If I get MERS, will I die?

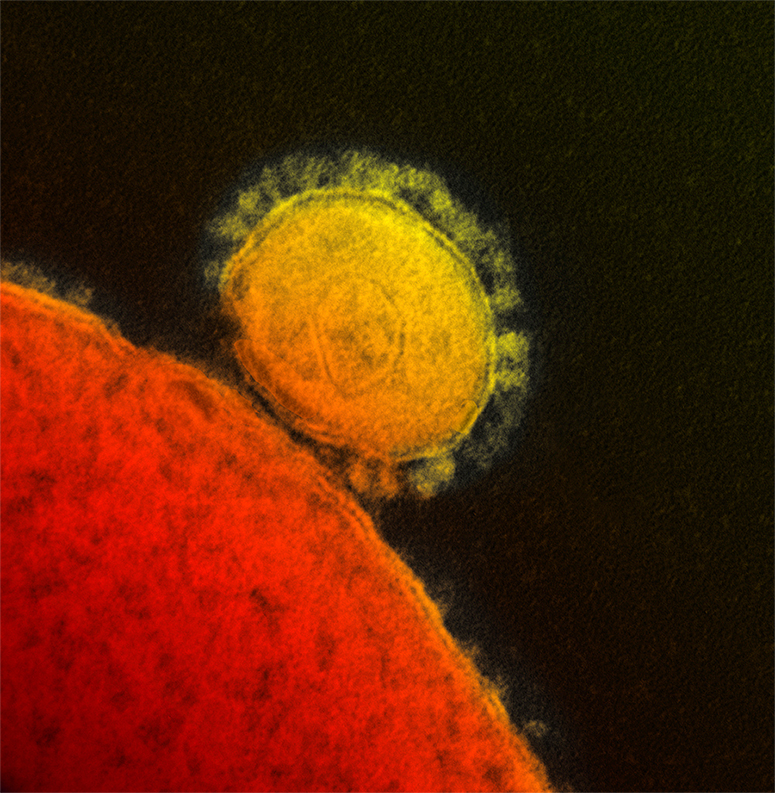

MERS coronavirus. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Calculating an actual death rate for MERS is currently impossible because there isn't enough data to know exactly how many people have been infected with MERS.

The World Health Organization reports at least 572 confirmed cases of MERS, about a third of which have been fatal. (The official death rate for SARS was about 10 percent, which gives you an idea of why experts are concerned about MERS.)

However, there could be many people with MERS and mild symptoms who never appear at a hospital, never get screened, and never get diagnosed. As surveillance increases and more doctors know to test for MERS, the apparent death rate might go down. (In fact, this may already be happening.)

To sum up: these numbers don't mean that an individual person's actual chance of dying is one in three. No one knows what that actual number is.

What happened to the people with MERS in the US? Did they die?

As of May 15, one has been released from the hospital and is fully recovered. The other is in the hospital and doing well.

What's the treatment for MERS?

There's currently no treatment specifically for MERS and no vaccine for it, either. If people do create a vaccine, there's a good chance they will give it to camels (just like they currently vaccinate poultry for bird flu).

Why are there all of these terrible viruses lately?

Experts point to several possible reasons that could all be contributing to the rise. As the human population grows, we've been physically expanding into other animals' territories. This proximity could be increasing how often viruses jump from animals to people.

What's more, once a virus is around people, increased air travel gives it a better chance to spread across the globe. Also, public health officials have been making a bigger effort to track these kinds of viruses lately (especially after the SARS outbreak in 2002–2003) — so part of the increase may be that they're discovering more about what is out there.

Culled From www.vox.com

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home