The National Homegrown Feeding Programme was launched in 2016 to, among other ideals, improve school enrolment and reduce child labour. What impact has it had so far? Are the goals being met? What are the hindrances? FEMI OWOLABI tours seven local government areas of Zamfara for an on-the-ground assessment of the programme. His findings provoke both cheers and jeers

Report Highlights

Feeding for Zamfara pupils lasted for just 10 days owing to “hiccups”School enrolment and attendance increased while it lastedMany local government areas were not covered in the roll-outFG says programme has resumed but schools deny the claim

Mariam Musa, a seven-year-old primary one pupil of Mareri Model Primary School in Gusau, Zamfara state, is gradually becoming less enthusiastic about school since she resumed this term.

Barely two weeks into the previous term, Musa and her classmates started enjoying a meal per day at school, and expectedly, the pupils’ love for school grew. Indeed, this was a cardinal aim when the APC-led federal government — as part of its campaign promises to provide a meal per day for public school pupils — launched implementation plan for the National Homegrown Feeding Programme, one year after it assumed power.

Placing emphasis on four main benefits, Nigeria’s vice-president, Yemi Osinbajo, whose office anchors the project, listed improvement of school enrolment and completion as first, adding that the project would also curb the current dropout rates from primary school estimated at 30% and thereby reduce child labour.

Class 1 pupils of Mareri model primary school… waiting for Godot

Out of the N6 trillion 2016 budget, N500 billion — of which N93.1 billion is mainly for the feeding — has been devoted to the social investment programme, Osinbajo disclosed at the launching in June 2016.

However, for pupils of Mareri Model Primary School, Gusau, Zamfara state capital, there is no more rice and beans for Mondays, no more moi-moi and pap for Tuesdays, no more yam for Wednesdays, no more kunnu for Thursdays, and Mariam Musa’s favorite, potato porridge that she always looked forward to eating on Fridays is no more.

“School is not interesting again,” Musa, who is one of the few pupils who have stayed in school since the feeding programme stopped, tells TheCable.

The feeding lasted for only 10 days in Zamfara, with hopes that it would resume someday.

‘I WAS LESS BURDENED UNTIL THE FEEDING STOPPED’

Sa’adatu Abdullahi: A widow who was relieved of her burden for 10 days

What a joyful moment for Sa’adatu Abdullahi, widow and a mother of five, one Friday afternoon in second term when three of her children— enrolled at the Ibrahim Gusau Model Primary School — returned home with filled stomachs. Since she lost her husband years ago, feeding her kids had been a burden for a woman whose survival depended on the little she got plaiting women’s hair in Lalan neighborhood where she lives.

“In the morning, I do give them N20 for breakfast, and I know this is not enough to buy a plate,” Abdullahi explains. And all the widow could do was to pray that more women came around to make their hair so she can have money to prepare meal for her kids when they return from school.

“I was so happy and I became less burdened when government started feeding my children in school,” Abdullahi says. Before she got up, her children were already set for school, most importantly, set for the breakfast offered in school.

“Zainab would even dress to go to school on Saturdays,” Abdullahi says of her second daughter.

Things took a sad turn for Sa’adatu Abdullahi when, suddenly, her kids returned home with empty stomachs. “I don’t really know what to do now,” cries the widow who has been struggling with her kids’ breakfast since the school feeding stopped. She is more worried about Zainab whose school attendance is now irregular.

“I was always happy going to school when they were giving us food,” Zainab, the primary two pupil, says. The lad who is shy to expressly say it, however, nods when asked if the school feeding — which has stopped— is the reason for her irregular school attendance.

‘I NOW STAY BACK ON MY MOTHER’S FARM’

Abdulrahman on his mother’s farm as free food is suspended

Abdulrahman is the “naughty boy” who would deploy all tactics to ensure he tastes out of the food meant for pupils in primary one to three. The National Homegrown Feeding Programme had made provisions for the feeding of only pupils in primary one to three, but Abdulrahman, a primary five pupil, joined the queue whenever the break time bell was jingled.

“I can’t imagine myself not eating from that food,” Abdulrahman says, his smile widening into a grin. He could not understand why the feeding wasn’t extended to pupils in higher classes.

“I am not the only one who did this,” he explains. “I used to see my other classmates, too, hiding in the feeding queue meant for pupils in lower classes.”

On a few occasions, when he was caught, pulled out of the queue, and flogged, Abdulrahman would drag his younger brother — who is legitimately entitled to a plate — into a corner, and beg that they both eat the food.

“Since the feeding stopped, I spend more time now, assisting my mother on her farm,” Abdulrahman tells TheCable. “When the feeding was ongoing, nothing could have stopped me from going to school,” he adds.

‘PLEASE, WHEN IS GOVERNMENT BRINGING OUR OWN FOOD?’

Pupils of Danbaza Model Primary School still waiting to be fed

While most schools in Gusau enjoyed the feeding for the days it lasted, pupils of Danbaza Model Primary School in Maradu local government could only wish they got fed, even if for a day.

“Maybe we are yet to start here,” Umar Sani, the school’s assistant head teacher tells TheCable. “We have heard about it since, but we have not seen any vendor bringing food to the school, not for a single day! We have been here, hoping and praying that the feeding project will get to us, but our excitement started fading when we were told that the feeding had already ended.”

The teachers couldn’t manage the pupils’ outburst one morning when a bus, loaded with food coolers, “mistakenly” veered into their school premises.

“You know, these pupils have been eagerly expecting federal government’s food — since their friends in other schools had started benefitting — and when they sighted that bus, they all ran outside with shouts of joy,” Sani explains. The bus didn’t wait a minute when it reversed and zoomed off.

“Sorry, not for your school!” the pupils, whose hopes had risen to the sky, were told.

“Only a few schools in Maradu town, the local government headquarters, benefited from this feeding,” Sani says, adding that, “nearby schools like Gidan Kano Primary School, Barkin Gudu Primary School, Bakaso Primary School and many others share the same fate with our school.”

He notes that barely 20 out of about 70 schools in the entire local government benefited from the feeding programme.

Unsure of why their school and others were exempted, teachers in Danbaza Model Primary School, however, think this could be as a result of not paying vendors attached to the schools.

“Initially, five vendors were attached to this school to bring food for the pupils,” one of the teachers reveals. “We heard that only one out of these vendors got paid by the government, and even that one vendor never delivered the food to this school.”

The school management, seeking explanation on why it was exempted, had written to its LGEA, but a source there told one of the teachers not to expect anything as the feeding programme was largely handled by greedy politicians who cared less, whether or not the food got to the pupils.

In Maru, a neighboring local government area, one official tells TheCable that about seven schools in the local government never benefited from the ten days feeding.

“Months ago, I was here at the local government secretariat when the feeding programme was launched,” he says. “And all the schools in the local government area were listed as beneficiaries, but the food didn’t get to seven of these schools during the ten working days that the programme lasted.”

He adds that the feeding programme only did well in the first five days, as most of the food vendors did not return the following week.

“I feel cheated and sad,” Nusaiba Rabiu, a primary one pupil of Danbaza Model Primary school says. And, lifting her face to TheCable’s correspondent, the little girl asks, “please, when is the government bringing our own food?”

ATTENDANCE AND ENROLMENT REDUCED

Dolen Yankaba Model Primary School under lock

On a shining Monday morning when pupils are expected to be in school, Dolen Yankaba Model Primary School in Kaura Namoda local government area is under lock.

“They have stopped coming to school,” Aminu Mohammed, one of the two teachers lounging under the shade in front of the locked classrooms says. “All of them, they stopped coming since the feeding stopped,” he adds, with a faint voice. And pointing at the expanse of farmland stretching from the school field, Mohammed says, “they’ve all gone back to the farm.”

The teacher explains that despite their efforts at getting them back to school, their parents who now use them on the farms have not been cooperating. During the ten days that the school feeding lasted, the pupils’ attendance was 267, but as soon as the feeding stopped, barely 30 pupils had marked themselves present since the term began.

A few miles away from the school, one of the pupils, with dusty legs, is seen with a hoe strapped to his shoulder. “My father said I should come with him to the farm, because there is no more food in school,” he shrugs, with a flash of smile.

Aminu Mohammed has been overwhelmed with sadness. Since the term began, all he comes to school to do is sit idly under the shade. “The joy of a teacher is having pupils to teach,” he says. “Whatever it will cost the government, please let them bring back the food!”

In Kaiwalamba Model Primary School, Kurmi local government area, Yahaya Hassan, the school’s head teacher now stands in front of the school, waiting, daily, endlessly for pupils come to school. “When the feeding was on, the attendance was 136,” he says. “But, I have not counted 60 pupils this term, and I wished that the feeding didn’t stop. It has affected the attendance of pupils in all the schools in Zurmi local government.”

Yahaya Hassan, head teacher, now stands in front of the school, waiting, daily, endlessly for pupils come to school

Hassan also cries out that his teachers have stopped coming since there are no pupils to teach.

“For these children to come back, that food must come back!,” his voice rises, almost to a scream.

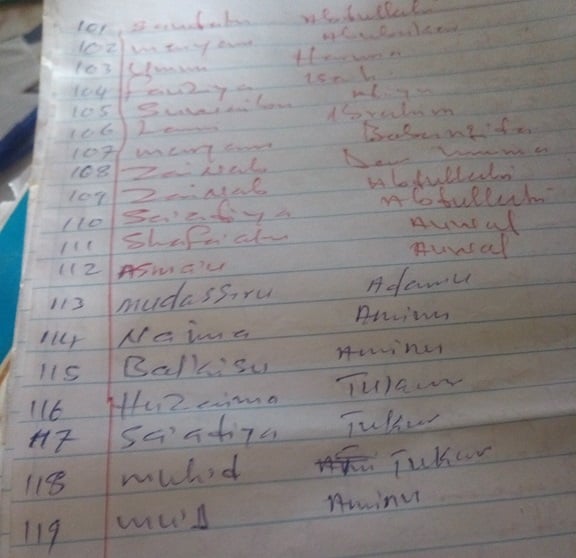

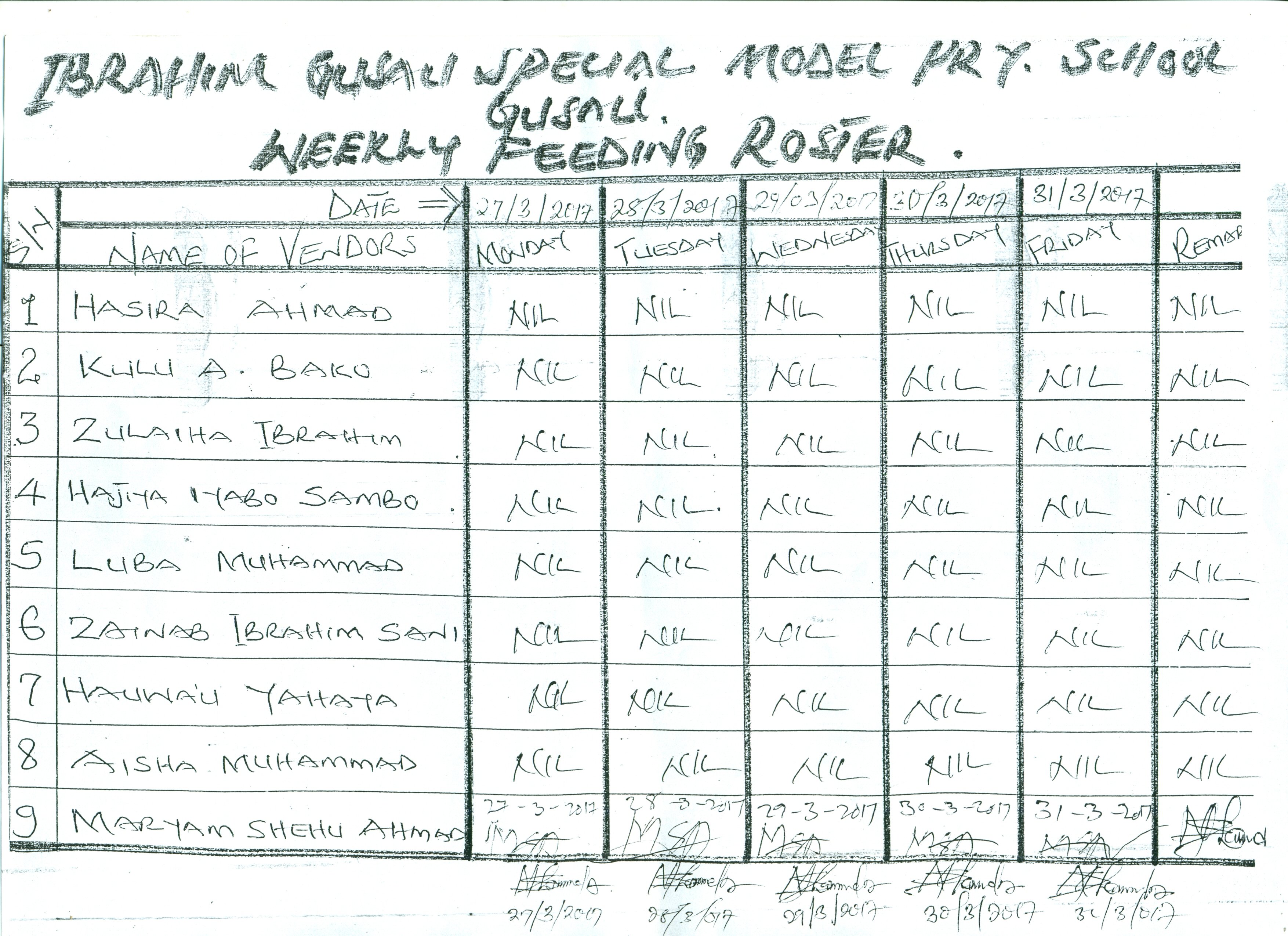

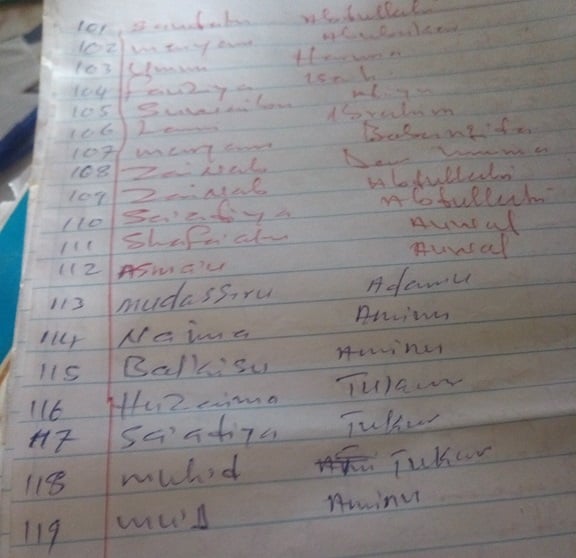

Kwangwami Model Primary School in Moriki ward has not fared differently. “In the first week that the feeding started here, I was so excited to see 119 pupils enrolled in my school, and that was for primary one only,” Faisal Umar, the school’s head teacher tells TheCable. Skeptical, however, the head teacher kept a temporary and separate register for the “119 pupils who joined the school because of food.” Many of his pupils who had stopped coming to school returned the week the feeding started, and the attendance was so overwhelming that the available classes barely contained them.

119 pupils who joined the school “because of food”

“They have all disappeared now, the 119,” Umar says, letting out a sigh. “In primary one, we had 71 pupils and additional 119 joined when the feeding started totaling 190, but right now, pupils in that class are not up to 70.”

Guara Guri Model Primary School, the second largest— after Magaji Gambo — in Shinkafi local government area has also witnessed a drop in school attendance and enrollment. “That feeding programme was the best thing that has happened to our pupils,” Nasiru Mu’azu, the school’s head teacher says. “Before the feeding started, the truancy was disturbing, but when the food came, the classrooms got filled. Seeing my school filled with pupils made me the happiest head teacher in the world.”

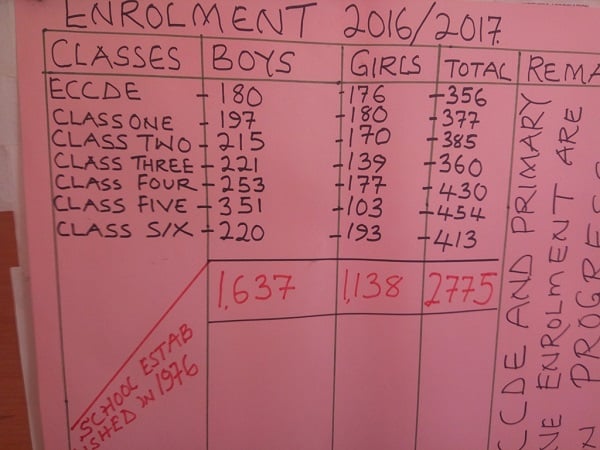

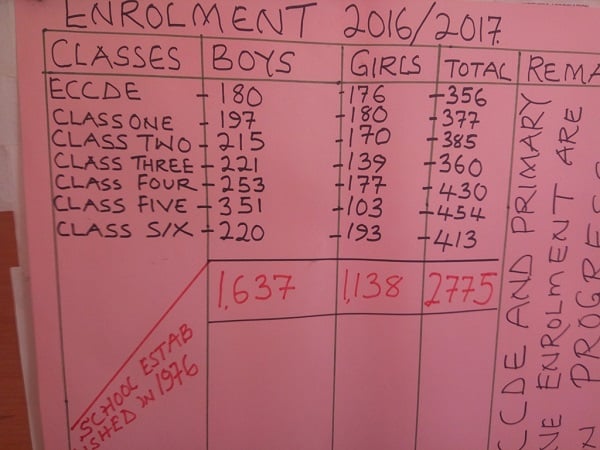

Enrollment increased at Guara Guri Model Primary School

Attendance increased from 2, 401 to 2, 775 in the ten feeding days. The figure, however, is fast dropping by the day, since the feeding stopped. “Many parents have been calling me to ask what has happened to the feeding programme,” Mu’azu says. “I have called the women leader to help us visit these parents and beg them to bring their children back to school, and even when I am not sure if this feeding programme will be brought back, I told the women leader to tell the parents that the children’s food is on the way.”

In Abubakar Tinua Model Primary School, Talata Mafara local government area, the assistant head teacher, Bashir Issa describes the attendance during the feeding days as overpopulation. “In a class of 70, we were now having 150,” he says. “Parents from far and near started trooping in to have their children enrolled, and none of the pupils missed class periods.”

Without chairs to sit on, class got filled with pupils sitting on the bare floor. “During that feeding programme, I was grouping the class because they were too many to teach at once,” one of the teachers says. Many of them had since stopped coming.

No chairs to sit

“And, attendance has not only dropped in Abubakar Tinua Model Primary School, academic performance of pupils who chose to stay has dropped,” the teacher laments.

Pupils in Balgare Model Primary School, Bakura local government area come to school in the morning, and when it is time for break, they go home and wouldn’t return. “This wasn’t the case when the feeding was on,” Maidama Mohammed, the school’s head teacher tells TheCable.

“When it is 9:30am, break time, they will all run to their nearby houses to go and eat, and we teachers will be waiting endlessly for their return. Maybe 1 out of a class of 50 will try and come back after the break time. There was no reason for them to go home during break time when the government brought food for them. When they are done eating, they gladly return to their various classrooms. In fact, no pupil would risk running home.”

The attendance has reduced from 783 to 503.

PUPILS STILL COME TO SCHOOL WITH PLATES, HOPING TO BE FED

A school boy with his feeding bowl even after stoppage

It is break time at Yelwa Model Primary School, Talata Mafara local government area, and Bakiru Abdullahi, a primary 2 pupil— who is probably less worried about the meal per day that has stopped coming— sits atop the fence, sucking his mango. With the N5 he gets from his mother, he can always sort his feeding with one mango per day.

No worries, Bakiru Abdullahi has his mango

“Every morning, some of these pupils will come to my office to ask; Mallam are they bringing food for us today? And you see some of them coming to school with their plates,” Musa Dalkurma, the school’s head teacher explains. “And sadly, I don’t always have an answer.”

Dalkurma further explains that lately, they have been experiencing many cases of pupils coming to complain about stomachache and headache since the feeding stopped. “Throughout the ten days that the feeding lasted, there was nothing like headache or stomachache,” he says. “I was asking my teachers; please, what’s happening? I’ve not seen any pupil with stomachache and headache and they told me the food has been doing the magic.”

Since there is no more food or drugs, the head teacher now allows the pupil with aching heads and stomachs to go home. This is coming against his principle which wouldn’t allow any pupil leave the school until the closing time. “But, what can I do when they keep coming; Mallam, my head, Mallam, my stomach?”

Sadiq Ibrahim, a primary 2 pupil, does not come to school to attend classes. He is here now to sell mangoes to pupils who have the N5. He couldn’t have thought of this when the school feeding was going on. “My mother brings the mangoes from her farm, and she tells me to come and sell in school,” Ibrahim tells TheCable.

VENDORS NOT SHOWING UP, POLITICIANS STEAL THE MONEY

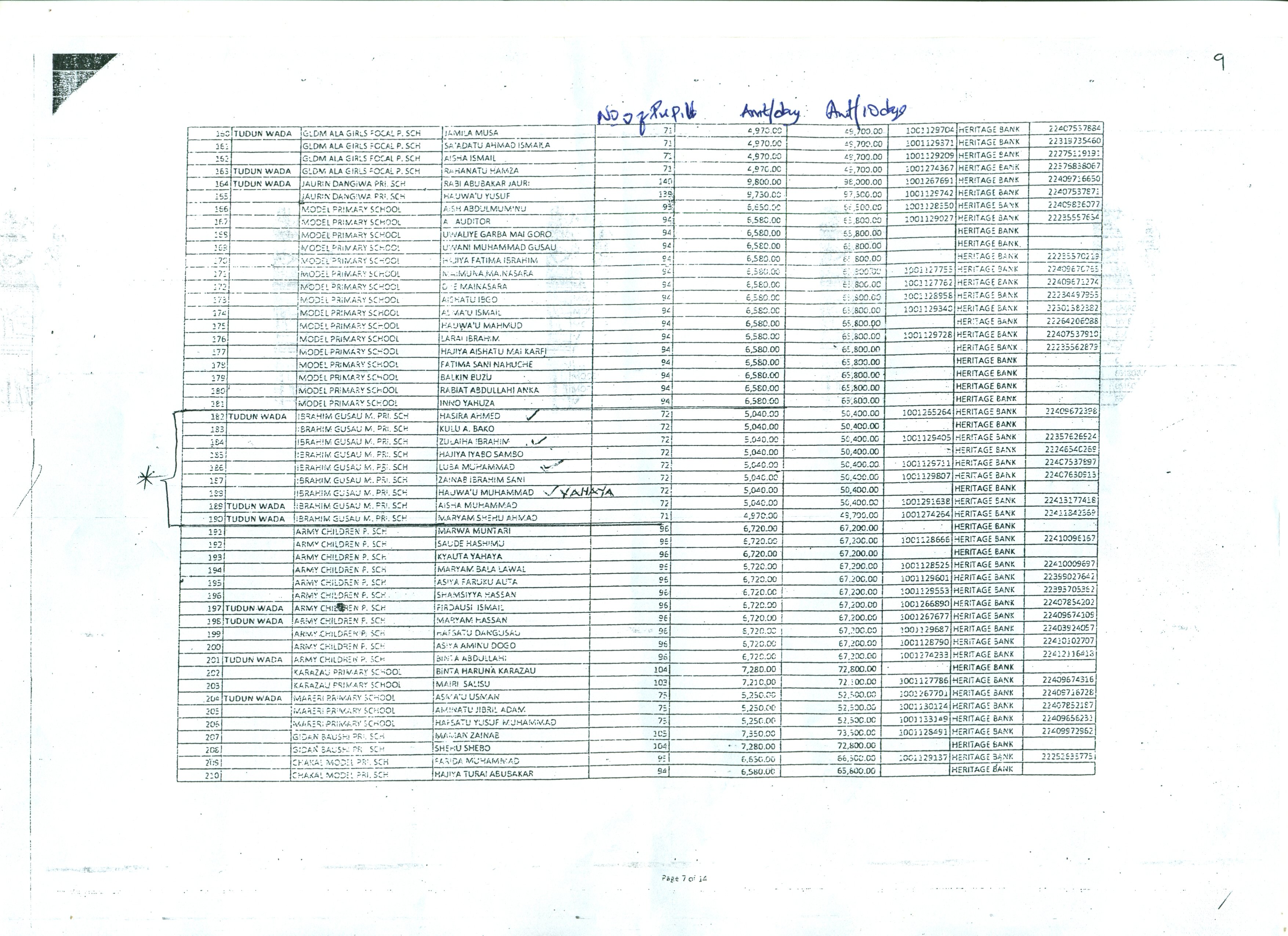

“N188, 765, 500m had been released to feed 269,665 pupils with 2,738 cooks in Zamfara State,” Laolu Akande, senior special assistant to the Vice-President on media and publicity, announced in February, 2017. The money is meant to feed the pupils for 10 school days.

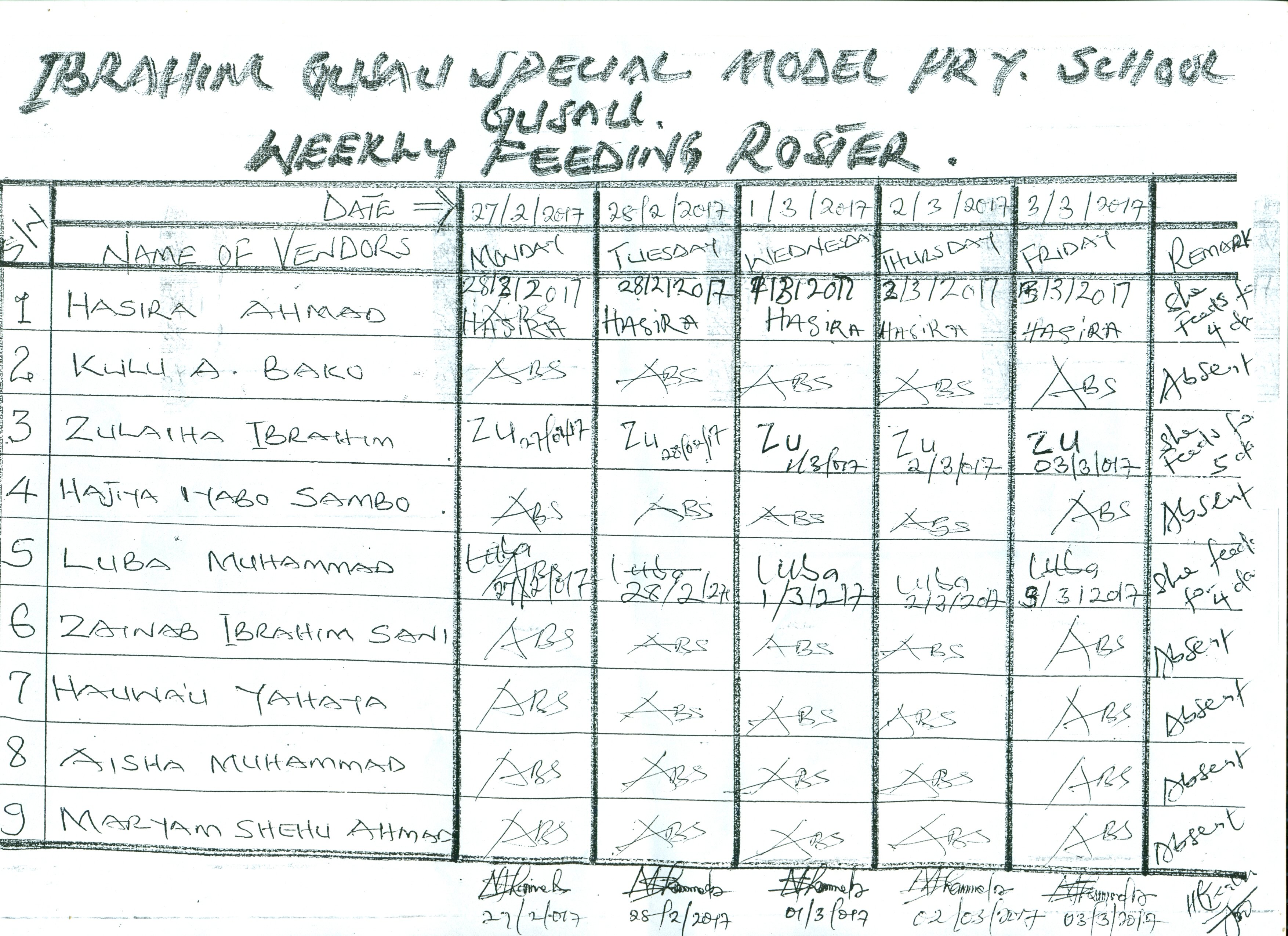

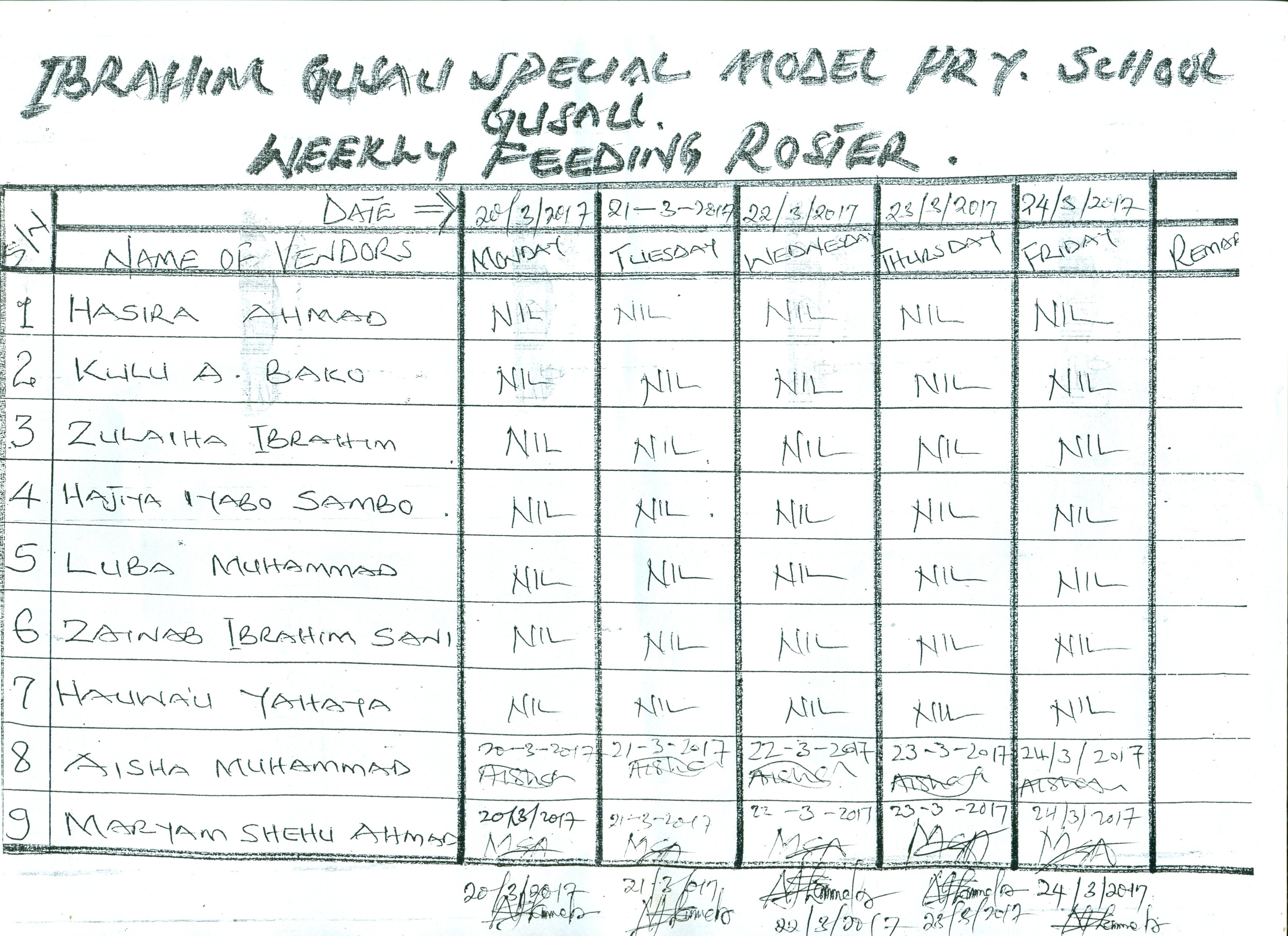

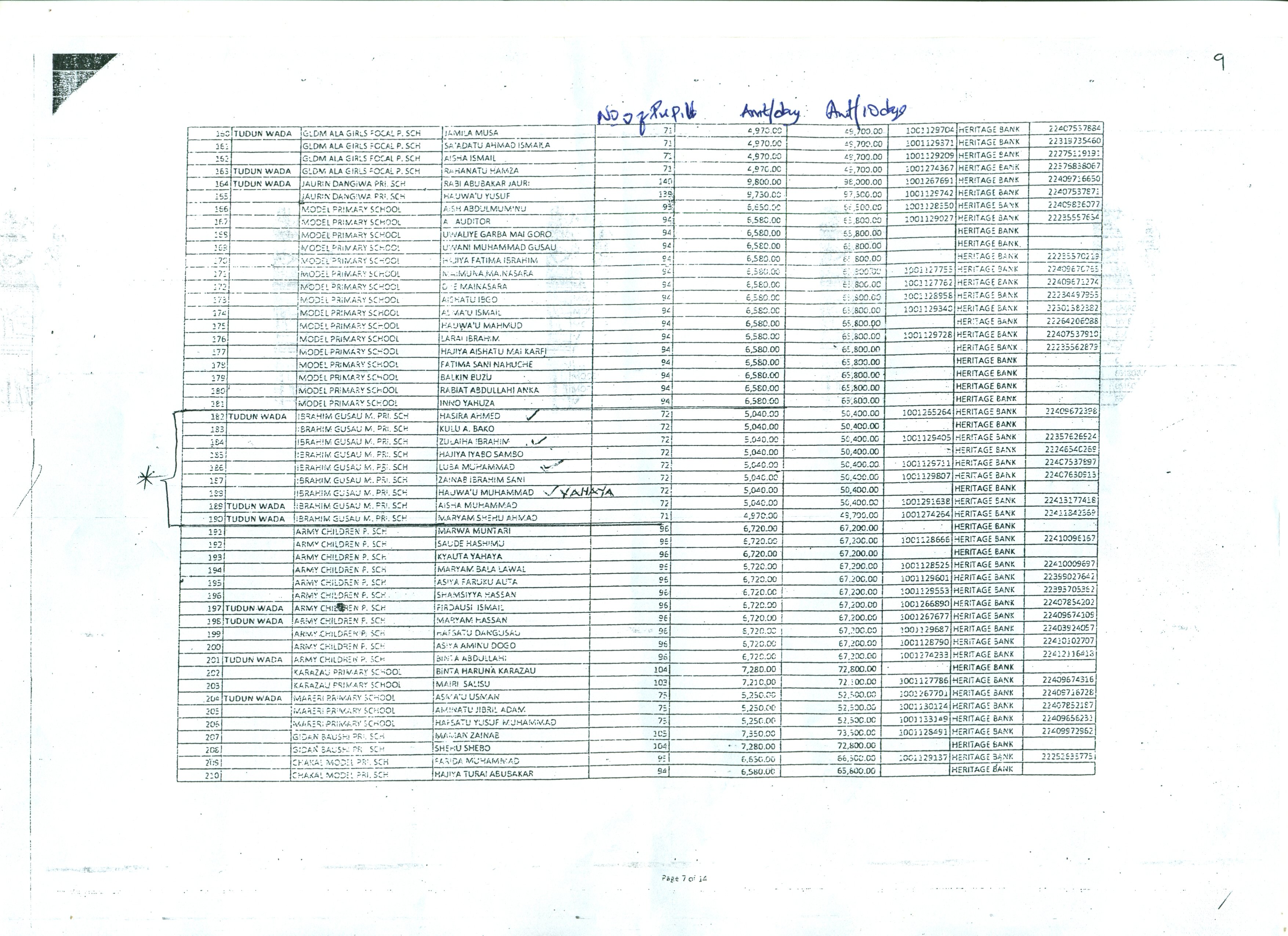

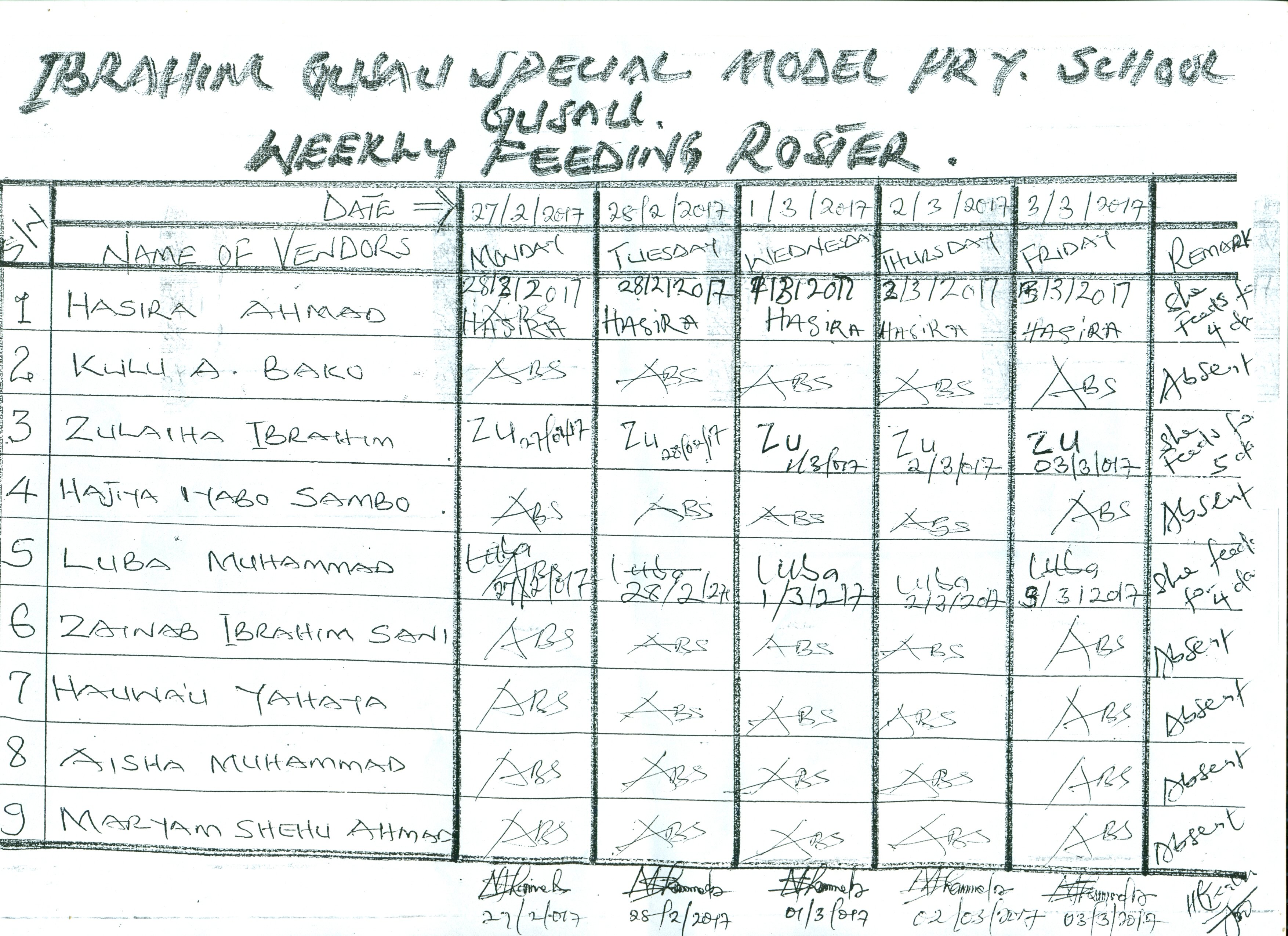

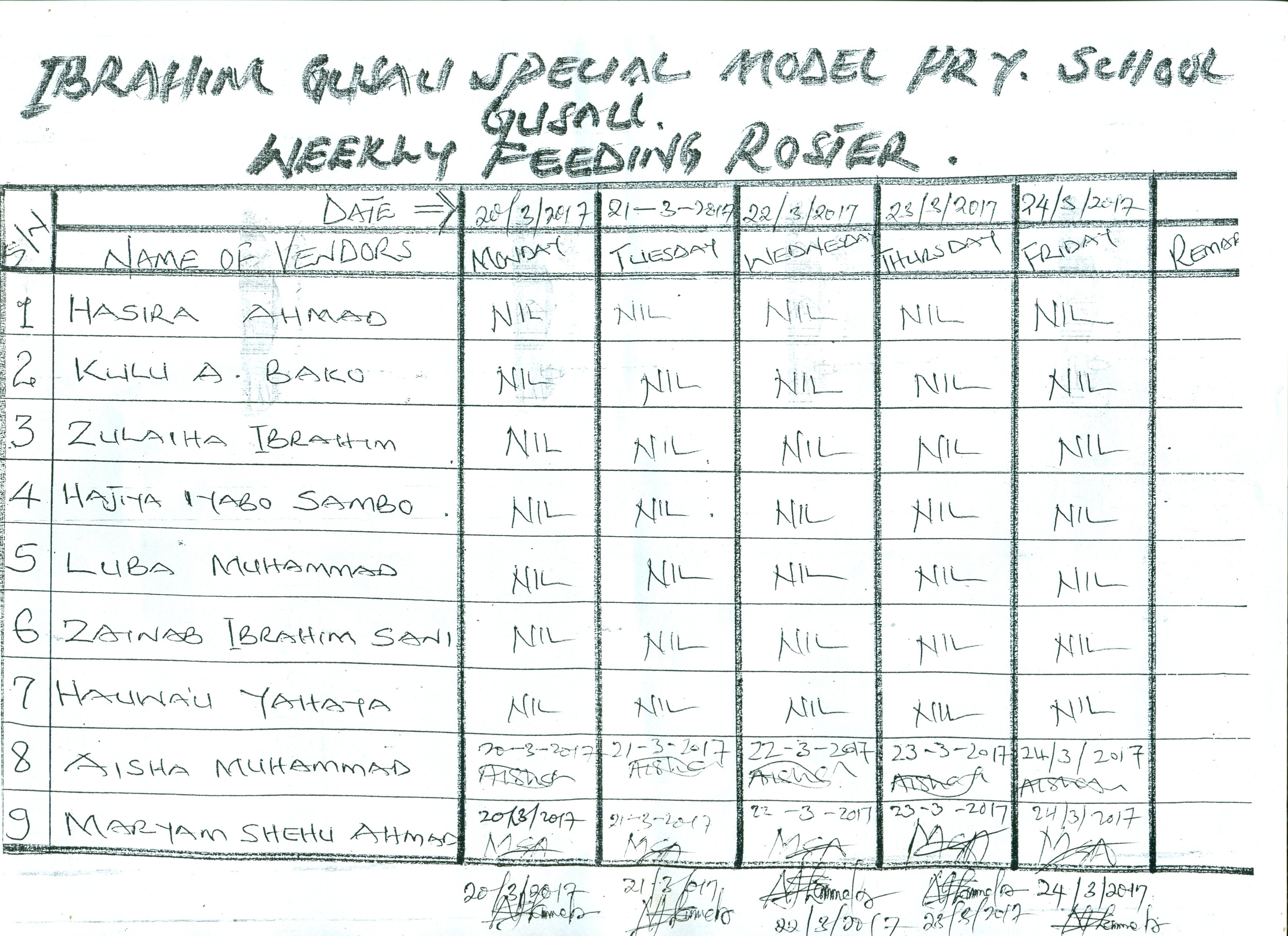

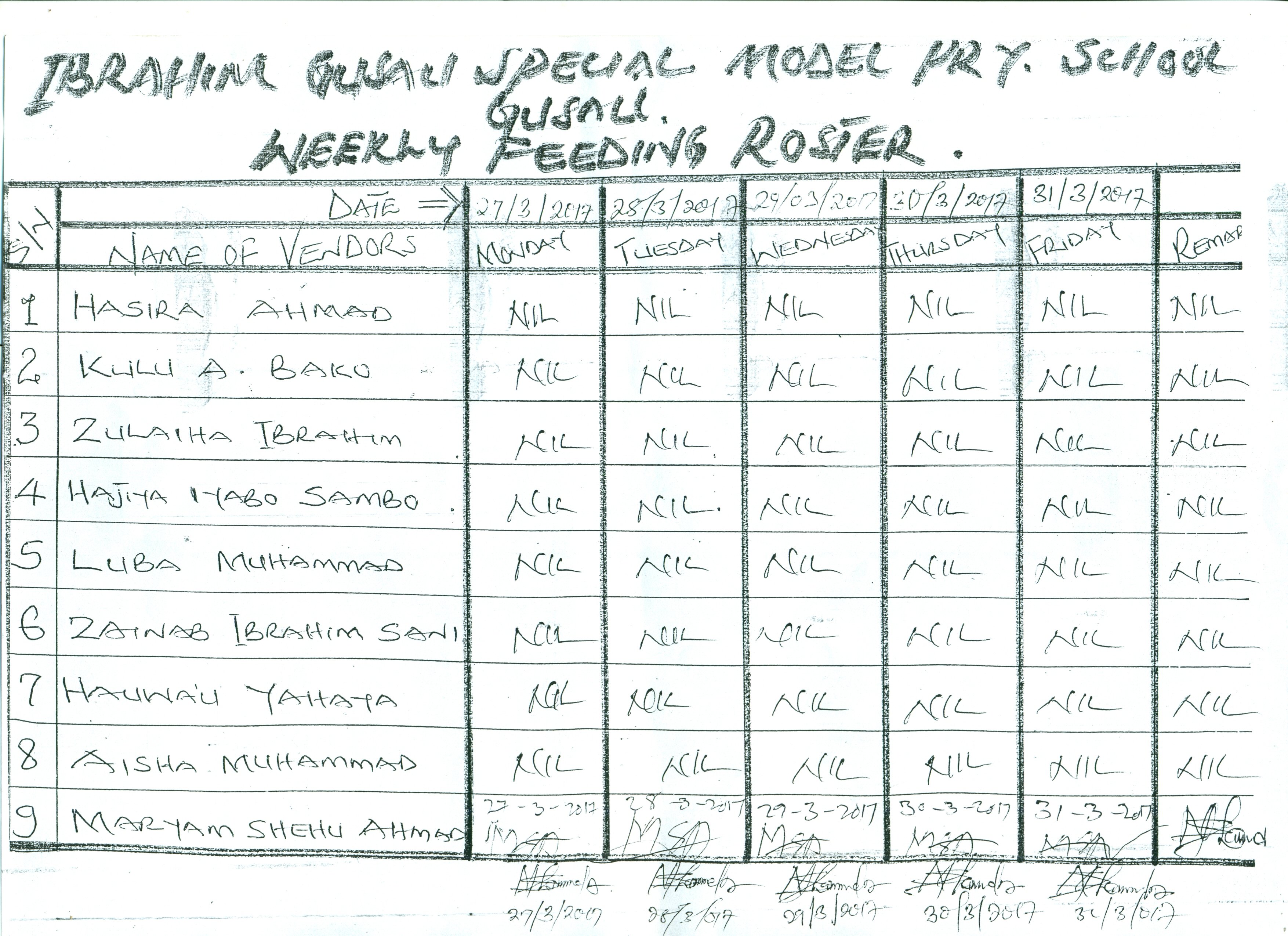

Like the cases with many other schools across the state, documents, exclusively, obtained by TheCable, show the irregularities in the food delivery of nine vendors attached to Ibrahim Gusau Model Primary School.

Hasira Ahmed who received N50, 400 at N5, 040 per day to feed 72 pupils for 10 days delivered for only 4 days. Zulaiha Ibrahim who, equally, received N50, 400 at N5, 040 per day to feed 72 pupils for 10 days was present for only 5 days. Luba Ibrahim with the same amount and number of pupils to feed brought food for 4 days only. Aisha Muhammad with the same amount came with food for 5 days, while only Maryam Shehu Ahmed who got N49, 700 at N4, 970 per day to feed 71 pupils delivered for the ten days the vendors were paid for.

Kulu Bako, Hajiya Iyabo Sambo, Zainab Ibrahim Sani and Hauwau Yahaya did not show up in any of the feeding days.

“These vendors who didn’t show up claim that they were not paid,” one of the teachers tells TheCable. “And the bank, on the other hand, insists that it has paid them.”

Attempting to point at the seeming corruption that may have been responsible for this, the teacher says most of the vendors, who were actually nominated by politicians, have been compelled to give a certain cut from whatever the government paid into their accounts for the pupils’ feeding. “It was discovered that most of the ward councilors and local politicians collected the money, and only left a little for the vendors. A particular politician collected the money, gave only N5, 000 to the vendors to buy potatoes to cook for the pupils, and that is why, if you go round the schools, you will see cases where a vendor brought food for only one day, some didn’t show up at all, and only a few delivered for the ten days that were paid for.”

He further explains that these politicians went to the designated [Heritage] bank with their nominated-vendors to open the mandated account, and they closely monitored payment into the account. “When payment is made, they go again with the vendors to the bank to make withdrawals and there, they take their own share with almost nothing left for the vendors to do their job.

“The state’s head of service summoned the bank manager to answer questions on why some of the vendors did not get paid, and the manger brought the payroll showing how payments have been made to the vendors. The school feeding programe manager, however, faulted the payroll, that some vendors’ names appeared multiple times.”

802 pupils were meant to benefit from the feeding in Ibrahim Gusau Model Primary School, but arrangements, on the document the school received, were made for 648. “We complained about this, and the programme manager said it was our LGEA that submitted that number of pupils.”

In Yelwa Model Primary School, Talata Mafara local government area, records made available by the head teacher show that out of 21 food vendors attached to the school, only 14 came.

For Guara Guri Model Primary School in Shinkafi local government area, 15 names of food vendors were received, but only 10 showed up. “We don’t know why the other vendors didn’t come, and nobody gave us an explanation as to why,” says Nasiru Mu’azu, the school’s head teacher.

Of the 24 food vendors assigned to feed pupils in Abubakar Tinua Model Primary School in Talata Mafara local government area, only 14 of them were seen. “And not all the 14 brought food for the complete 10 days,” Bashir Mohammed, the head teacher says.

Tucked inside a remote part of Zurmi local government area, Kaiwalamba Model Primary School got only one vendor to provide food for its pupils. Sadly, however, the vendor was shortchanged and what she brought wasn’t just enough to go round.

“The vendor was handed N41,000 out of N48,000 the federal government gave,” Yahaya Hassan, the school’s head teacher reveals. “It was to feed about 130 primary 1 to 3 pupils. And when this N48,000, in the first place not enough money to feed these pupils, we were shocked that the vendor didn’t get the complete money. The people who went to the bank to collect the money on the vendor’s behalf took N7, 000 out of the money.”

Zurmi, Maru, Shinkafi, Talata Mafara, Maradu and Gusau local government areas, TheCable gathers, are the areas where this form of stealing by the politicians is prevalent.

‘WE DON’T KNOW WHY THE FEEDING STOPPED’

Ibrahim Gusau Model Primary School sign board

The head teacher of Ibrahim Gusau Model Primary School, Aminu Balarabe and his counterpart in Mareri Model Primary School, both in the state capital, do not really know why the school feeding stopped, too suddenly. “The programme started here last term, on a Friday that ended the second week,” Balarabe explains. Like most head teachers in Zamfara state, Balarabe was not in the know of the feeding project; how it all began and why it has now stopped. The head teachers claim that they did not receive any form of written notification when the feeding started and when it would abruptly end.

“Although, we have heard that Zamfara state will be one of the beneficiaries of the National Home Grown School Feeding Programme, we just came to school that Friday and when it was time for break, we saw these vendors coming in with coolers of food,” Balarabe further explains.

Mareri head teacher who waited to hear from either the Local Government Education Authority (LGEA) or State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) now concludes that these two key stakeholders in the state’s primary education do not have information on why the school feeding stopped.

“This whole thing is the arrangement of politicians, and we just don’t know anything!” booms one of the head teachers in Talata Mafara local government area. “Even when some food vendors didn’t come, we didn’t know which quarters to report to,” he adds.

“Head teachers won’t know why the feeding stopped,” Muktar Lukar, Zamfara state’s commissioner for education tells TheCable. “It is above the information they would, normally, have received,” he adds. “The ministry of education is not the one running this programme, but I am worried, too, that my children have stopped getting the one meal per day in school.

“In the beginning, the ministry of education was fully involved as a stakeholder together with all the parastatals under the ministry, but eventually, the responsibility for championing the project wasn’t resident in the ministry.”

‘THIS IS WHY WE STOPPED THE FEEDING’

Zamfara state was one of the listed pilot states when funds were released in February, 2017 for the commencement of the National Homegrown Feeding Programme in Nigeria. Although, largely funded by the federal government, the programme was expected to get support from multinationals and state governments.

“When the programme got to Zamfara, the governor formed a committee,” explains Mohammed Abubakar, Zamfara state’s programme manager for the National Homegrown School Feeding Programme. “He called it the steering committee that would look into this feeding programme.

“The committee was mandated, amongst other things, to identify and liaise with the MDAs (ministries, departments and agencies) since the programme is a multi-sectoral one. The programme would involve ministries and departments relevant to the programme, and this include; ministry of education, women affairs, agriculture, local government affairs, health, finance and the universal basic education board.”

The ministry of women affairs is to identify women who can be engaged as food vendors. That of health is to develop nutrition guide for locally prepared food. Agriculture is to provide the farmers who would supply the cooks. Budget and finance is to design the template and framework to run with. Education, being the key stakeholder—universal basic board especially— is to submit figures of pupils to be fed.

“The problem started when each ministry started claiming that it owned the programme,” Abubakar says. “Ministry of education attempted to take ownership because they think they believe the programme is about them. But then, where are the farmers, the food vendors? Because of the greed of most of our executives, they all wanted the programme to be solely handled by their ministry.”

Chaired by the highest political office holder from the local government area, committees were also set up in each local government area of the state. The committee which comprises the education secretary, principal medical officer and others selected the women who would serve as food vendors.

Attendance is dropping fast

“When these selections were made, the lists were sent to us,” Abubakar says. “We were then asked to identify a bank for payment. The impression we got was that we should use only one bank and it is the reason we are in this present quagmire. The bank— Heritage Bank— was almost imposed on us by these people (politicians). We argued that Heritage Bank has only one branch in the entire state and it is here in Gusau, the state capital and we are to reach food vendors in 13 other local governments. They said they can mobilize agency banking across those local governments. So, by the time accounts were opened for these vendors, BVN (Bank Verification Number) generation became another problem.”

Most of the vendors, especially those in the remote areas know little or nothing about banking. “These women are not exposed to banking system,” Abubakar explains. “Somebody is bearing a name from her village and when she comes to the bank to get her account details, the bank asks her for means of identification and when she presents her voter’s card, the name does not correspond.

“When we sent food vendors’ details to our national office in Abuja, they forwarded it to the Nigerian Interbank Settlement System (NIBSS) for validation. And out of the 3, 664 names that were submitted, only 2, 738 got approved for payment.”

Abubakar believes that the payment process, for the 2, 738 vendors, was plagued by fraudulent activities by the bank. “We gave them (the bank) one week to pay these vendors,” he says. “They were supposed to simultaneously pay the vendors, but vendors from other local governments who didn’t see any agents of the bank in their villages, were forced to travel many kilometers to the only branch of bank in Gusau. They were subjected to inhumane treatments. At the end of one week, the bank couldn’t give us a comprehensive list of how many vendors they’ve paid and how much money left.

“Money has been sent to people’s account, and yet the bank wouldn’t notify them of exactly how much has been credited to their accounts. About three times, they’ve submitted statements on how they’ve made payments to vendors but the statements have been fraudulent. Replication of names, distortion of figures were discovered when we subjected these things to scrutiny.

“We are not involved in the disbursements of the money, because some people think that the money was sent to us. As the state programme manager, I didn’t even know when Zamfara state got paid because the bank never told me. I got to know when I went to Abuja. All we do, on our own part, is to engage the food vendors, get the bank accounts opened, and we send their details— including the list of schools and number of pupils to supply— to the National Homegrown School Feeding Programme office in Abuja. They will submit it to their own budget office and then the budget office sends to NIBSS, and then money is sent directly to the validated accounts.”

Abubakar who doesn’t want anything to taint his integrity, wrote a letter to the national office in Abuja, asking that Zamfara state be placed on hold while they get another bank to engage. “This is why the feeding programme is on hold now,” he says. “We also lodged a complaint that our money that is left in that bank must be given to us.”

The request to change from Heritage Bank to another has been granted. “We are looking at engaging First Bank that has branches in about 7 local government areas in the state,” Abubakar explains. “It will be easier for the vendors to get their money without the stress and cost of travelling to Gusau.”

Corroborating the findings of TheCable, Abubakar says some of the local politicians, too, have been involved in the fraud. “Ward councilors whom we thought are closer to the people and given the opportunity to bring in vendors, brought in their own people because of what they wanted to gain,” he says.

“Our politicians are the real enemies. A lot of schools came to us— that they’ve not seen food, and by our records, vendors attached to those schools have been paid. We discovered that these councilors actually collected the money and pupils were not fed. I went round myself and I detected this, even in Gusau here. Some of them take the money as national cake. We have identified some of them and as I speak, we are sending a petition to the EFCC.”

Abubakar, however, expects that in the coming weeks, food vendors across the 14 local governments would get paid for the second part of the project, and pupils will return to enjoying their one meal per day.

The programme manager, touching other issues, says their job which is monitoring and evaluation has not been an easy one, owing to lack of logistics. “While the programme is being funded by the federal government, it is the duty of state governments to provide monitoring and evaluation,” he explains.

“The state is to provide the progmame office and its staff, and all that the office needs to properly function. The federal government does not give us a kobo. The money they send goes directly to the vendor, and it’s meant to feed the pupils. We, under the employment of the state, are the ones to go out and check if a vendor who has been paid has delivered food or not. But, we don’t have the logistics to cover all the local governments and because the federal government is not bothered about how we run the office, we can only manage with the little that is provided by the state government. We don’t even have vehicles to move around for the monitoring.”

‘SBMC SHOULD BE CARRIED ALONG’

The National Homegrown School Feeding Programme in Zamfara state perhaps could have been more successful if members of the School Based Management Committee (SBMC) are involved, this, the position of many teachers in Zamfara state.

“Every school has SBMC, comprising teachers and parents, and it is more structured and closer to the pupils,” one of the teachers tells TheCable. He explains that the disconnection between the programme and SBMC has resulted in some vendors bringing food that pupils are not familiar with. “For days, they were bringing alala for my pupils and this is not the local food here,” he says.

Bala Abubakar, the SBMC chairman for Namoda Model Primary School in Kaura local government area, argues that the feeding programme can only be sustained if SBMC is fully involved, especially when its members are hired as cooks. “We don’t even know these women who bring food for our children,” he explains. “Some of the food vendors complained about the distance they travel to bring food, and the programme is supposedly designed to make use of food vendors within the school’s locality.”

Abubakar adds that mothers’ association, an arm of SBMC ought to have been engaged as cooks and not people picked by politicians. “Before this feeding started, the mothers’ association has always been in the advocacy for girl-child education and the association goes round the town just to persuade these children to come to school. When they brought the homegrown school feeding programme, none of these women was engaged. Why would they bring other women to feed our children when we have a mother’s association? The politicians picked their wives, girlfriends and daughters as the vendors. And we can’t trace vendors assigned and who didn’t show up. If this feeding programme must be sustained, government must get the SBMC involved,” he says.

Laolu Akande: The feeding has since resumed

Akande says the school feeding programme has since resumed in Zamfara state.

“It was paused because of banking delays in the payment of the cooks and other issues,” Akande says, adding that two new banks, with more branches across the state, have been engaged for effective and timely payment of the cooks.

A couple of head teachers in the state, however, tell TheCable that they are yet to see government school feeding vendors in their schools.

Of the tens of head teachers and teachers asked by TheCable to confirm Akande’s claim, only one in Shinkafi local government said, although he is yet to see the food, he has been notified that the programme will resume soon.

“I have neither seen the food nor been notified of it coming anytime soon,” a head teacher in one of the schools in Gusau, Zamfara state capital, tells TheCable.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not the views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Source The Cable

Labels: news, Politics

After several unsuccessful interventions to save a 13-year-old marriage between Mr Sunday Okafor and his wife, Adetola, an Igando Customary Court in Lagos State, has dissolved the union, on the account of the husband’s infidelity.

After several unsuccessful interventions to save a 13-year-old marriage between Mr Sunday Okafor and his wife, Adetola, an Igando Customary Court in Lagos State, has dissolved the union, on the account of the husband’s infidelity. FORMER member of the House of Representatives from Plateau State, Hon Simon Mwadkwon, has charged the leadership of the Peoples Democratic Party at the National level to work toward genuine reconciliation and bring everybody on board irrespective of the roles played during the crisis.

FORMER member of the House of Representatives from Plateau State, Hon Simon Mwadkwon, has charged the leadership of the Peoples Democratic Party at the National level to work toward genuine reconciliation and bring everybody on board irrespective of the roles played during the crisis.

Photo: Sylvester Okoruwa

Photo: Sylvester Okoruwa

Uduaghan and Utomi

Uduaghan and Utomi